Mẹo Which one of the following statements about the nurse and ethnocentrism is true?

Mẹo Hướng dẫn Which one of the following statements about the nurse and ethnocentrism is true? Mới Nhất

Lê Minh Châu đang tìm kiếm từ khóa Which one of the following statements about the nurse and ethnocentrism is true? được Cập Nhật vào lúc : 2022-12-01 23:56:04 . Với phương châm chia sẻ Bí kíp về trong nội dung bài viết một cách Chi Tiết 2022. Nếu sau khi tham khảo tài liệu vẫn ko hiểu thì hoàn toàn có thể lại Comments ở cuối bài để Ad lý giải và hướng dẫn lại nha.Celeste Cang-Wong, RN, MS Candidate, Susan O Murphy, RN, DNS, and Toby Adelman, RN, PhD

Nội dung chính Show- Celeste Cang-WongSusan O MurphyToby AdelmanIntroductionThe Changing Face of the Patient PopulationCultural Encounter as Workplace StressorFamily and Cultural SensitivityCommunication Across CulturesTheoretic PerspectiveResearch QuestionDisclosure StatementAcknowledgmentsThe Great ArmyWhat is true about the nurse and ethnocentrism?Which of the following statements about empathy is correct?Which of the following is the essential component The nurse must bring to the therapeutic nurseWhich of the following is the most important skill the nurse brings to the therapeutic nurse

Celeste Cang-Wong

Celeste Cang-Wong, RN, MS Candidate, is the Perioperative Nurse Manager for the Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara Medical Center, San Jose, CA. E-mail: [email protected]

Find articles by Celeste Cang-Wong

Susan O Murphy

Susan O Murphy, RN, DNS, is a Professor Emeritus in the School of Nursing, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. E-mail: [email protected]

Find articles by Susan O Murphy

Toby Adelman

Toby Adelman, RN, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the School of Nursing, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. E-mail: [email protected]

Find articles by Toby Adelman

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Celeste Cang-Wong, RN, MS Candidate, is the Perioperative Nurse Manager for the Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara Medical Center, San Jose, CA. E-mail: [email protected]

Susan O Murphy, RN, DNS, is a Professor Emeritus in the School of Nursing, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. E-mail: [email protected]

Toby Adelman, RN, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the School of Nursing, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. E-mail: [email protected]

Copyright © 2009 The Permanente Journal

Abstract

Objective: We explored nurses' experiences when they encounter patients from cultures other than their own and their perception of what helps them deliver culturally competent care.

Methods: Registered nurses from all shifts and units Kaiser Permanente Santa Clara Medical Center were invited to complete a questionnaire. Within the time frame allowed, 111 nurses participated by returning completed questionnaires.

A descriptive survey was conducted using a questionnaire that contained multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, and open-ended items.

Results: A large majority of respondents reported that they drew on prior experience, including experience with friends and family, and through their education and training, and more than half also included travel experience and information obtained through the Internet and news truyền thông. They also expressed a desire for more training and continuing education, exposure to more diverse cultures, and availability of more interpreters. When respondents were asked to enumerate the cultures from which their patients have come, their answers were very specific, revealing that these nurses understood culture as going beyond ethnicity to include religious groups, sexual orientation, and social class (eg, homeless).

Discussion: Our research confirmed our hypothesis that nurses are drawing heavily on prior experience, including family experiences and experiences with friends and coworkers from different cultures. Our findings also suggest that schools of nursing are providing valuable preparation for working with diverse populations. Our research was limited to one geographic area and by our purposeful exclusion of a demographic questionnaire. We recommend that this study be extended into other geographic areas. Our study also shows that nurses are drawing on their experiences in caring for patients from other cultures; therefore, we recommend that health care institutions consider exposing not only nurses but also other health care professionals to different cultures by creating activities that involve community projects in diverse communities, offering classes or seminars on different cultures and having an active cultural education program that would reach out to nurses. The experiences provided by such activities and programs would help nurses become more sensitive to the differences between cultures and not immediately judge patients or make assumptions about them.

Introduction

The Changing Face of the Patient Population

The cultural face of the America's population is changing. According to the US Census Bureau,1 one of every three persons in the US comes from an ethnicity other than non-Hispanic white. In Kaiser Permanente (KP), Santa Clara County, CA, we care for an especially diverse population. The most recent census,2 which was in 2006, showed that of the 1.7 million people in Santa Clara County, CA, 63% are white, 30.5% are Asian, 2.8% are black, 0.8% are American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.4% are native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and 2.5% are persons who identified with two or more races.

In 2004, the Kaiser Family Foundation published the Sullivan Commission Report,3 recommending the following three goals related to racial and ethnic diversity: First, all racial and ethnic groups in a community should be represented among health care professionals. Second, talents, skills, and ideas from ethnically different groups should be incorporated systemwide. Third, health care institutions should change the health care culture by promoting diversity through creating professional development opportunities. Overall, the commission3 emphasized the importance of increasing the representation of minorities in the workforce.

In some cultures, it is considered a moral responsibility for a family thành viên to be by a patient's side and to provide care.7–11

Despite this growing diversity in the US and in our service area, diversity among nurses has not kept up with that of the population. In many health care settings, nursing does not reflect the demographics of the general population. Even when nurses are well educated and culturally sensitive, the lack of ethnic diversity among them creates a challenge for those who are attempting to provide holistic care to an increasingly diverse group of patients. Holistic care is a term often used in nursing that means to care for patients in their entirety: body toàn thân, emotions, mind, and social and cultural, environmental, and spiritual aspects.

To develop an effective and therapeutic relationship with a patient, a nurse must establish trust and respect with the patient. Acknowledging a patient's individual cultural perspective is an important part in establishing this trust.4,5 Misunderstanding cultural differences can be a barrier to effective health care intervention and can even cause harm. This is especially true when a health care professional misinterprets or overlooks a patient's perspectives that are different from those of the health care professional.

Cultural Encounter as Workplace Stressor

Workplace stress has been defined as “the physical and emotional outcomes that occur when there is disparity between the demands of the job and the amount of control the individual has in meeting those demands.”6 Stress may occur when nurses are unable to provide the kind of care that is expected of them. If nurses are unprepared to giảm giá with cultural differences in the workplace, a stressful situation can result.

The presence of workplace stressors not only affects the delivery and quality of care but also creates unnecessary costs for the institution. When nurses are constantly exposed to stress, absenteeism increases and employee turnover may result, both of which can have a significant financial impact on the organization.

Family and Cultural Sensitivity

Family support during illness has unique meanings across cultures that help maintain integrity within the extended family, especially in an unfamiliar environment with norms and values that differ from those of the family. In caring for patients and interacting with families, nurses must demonstrate cultural sensitivity, respect diverse practices and beliefs, and understand how cultural differences might alter the way care is provided.

In some cultures, it is considered a moral responsibility for a family thành viên to be by a patient's side and to provide care.7–11 Family members may find it difficult to arrange transportation to and from distant medical facilities, to locate someone to stay with the patient, or to take care of children during a parent's hospitalization; in such a situation, they often rely on other members of their widely extended family. In some cultures, the family stays with the patient to ensure that if the patient dies, a family thành viên is there to hear the patient's last words.

Communication Across Cultures

Sensitivity to cultural needs, beliefs, and values, including in communication, is essential for nursing interventions to be effective.12 Communication is the central factor in providing transcultural care.13 One of the most obvious challenges occurs when a nurse and a patient do not speak the same language. Non-native English-speaking patients or nurses may have to process English conversation in their native tongue—interpreting word for word, thinking in their native tongue, and then trying to make sense of their thoughts before expressing them.14 In the meantime, there may be an uncomfortable silence and a delay in response, which the patient may misinterpret.

It is difficult to give timely care when the nurse has to look for a certified interpreter the hospital. Nailon15 studied the experiences of Emergency Department (ED) nurses when dealing with non-English-speaking Latino patients. She found that there was often a delay in care because nurses had to interrupt their nursing assessment to look for a translator who was not always available. Sometimes the nurses checked vital signs and reviewed the test results, choosing to secure a translator later when a physician would be ready to assess the patient. The nurses expressed their concern that care was delayed because of a lack of interpreters, especially in a setting with a great many patients requiring acute care. It was also a concern that nurses were using family members as interpreters, because patients might have withheld some information because they knew that it could affect their relationship to the family. Other times, nurses did not use telephone translators, even when such aid was readily available; instead, they tried to communicate using their limited Spanish vocabulary. Sometimes nurses would ask a staff thành viên who was not formally trained to interpret. Using an interpreter who is not formally trained may result in inaccurately interpreted messages; if nurses cannot verify patient responses, there is no assurance that the message was accurate.

Another way of communicating cultural needs among staff is through a patient's medical record (charting). Such documentation can help promote cultural sensitivity and foster continuity of care.16

Theoretic Perspective

Generally, the provider's attitudes and personal biases are the primary barrier to culturally competent care. Several conceptual frameworks have been proposed to support the development of greater cultural sensitivity in delivery of health care.12,17–19 The common denominators among these models and frameworks include gaining self awareness, checking for personal biases, avoiding the tendency to stereotype, and refraining from discrimination. An introspective examination of this kind is, of course, challenging, especially for health care professionals who have limited transcultural experience or have not been trained in dealing with cultures different from their own.

In developing the ACCESS (assessment, communication, cultural negotiations and compromise, establishing respect, sensitivity, and safety) model for providing health care, Narayanasamy20 explored nurses' responses to the cultural needs of their patients. Nurses were asked to give an example of a nursing situation in which cultural care was given. On the basis of the data, Narayanasamy reported that the nurses tended to associate cultural needs with food or religion. Even though the study suggested that nurses recognize cultural needs and that they actively practiced culturally sensitive care, such care was interpreted within a more narrow understanding.20

Research Question

Our study built on the work of Narayanasamy20 in 2003, in that we wanted to gain a greater understanding of nurses' cultural awareness by asking nurses to describe their own experiences with diverse patients and families. Specifically, the aim of our study was to explore how nurses know how to care for patients from cultures different from their own. Given the growing diversity of our patient population, we sought to clarify what nurses draw on in taking care of patents from multiple cultures. We hypothesized that many of the ways they do so are drawn from personal or professional experience and exposure to other cultures, as well as from formal education.

Methods

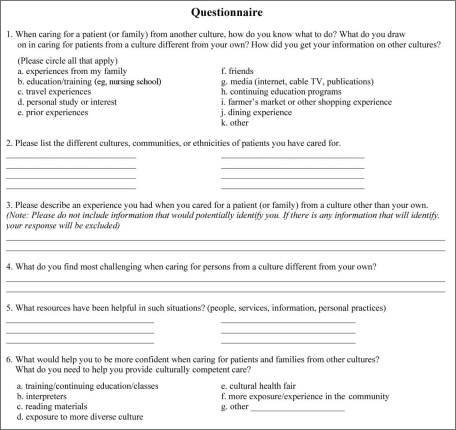

We developed a questionnaire to inquire how nurses responded to transcultural encounters. It included multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, and open-ended questions (Figure 1). This format invited nurses to speak for themselves about what they saw as culturally important and unique experiences. (The responses to the multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank questions are reported here; the open-ended responses will be reported in a subsequent article.)

Open in a separate window

Figure 1.

Survey questionnaire.

The common denominators among these models and frameworks include gaining self awareness, checking for personal biases, avoiding the tendency to stereotype, and refraining from discrimination.

Approval for the study was obtained from both the KP Northern California institutional review board (IRB) and the IRB of the university in our service area. Questionnaires were distributed to 250 registered nurses from KP Santa Clara Medical Center. Nurses were recruited from all shifts and units (including the ED, critical care, pediatrics, maternal and child, medical surgical, telemetry and step-down units, and the perioperative department). A letter of information was attached to the questionnaire, outlining the purpose of the study, explaining that respondents would remain anonymous, and inviting participants to return their completed surveys to a designated box on each unit.

Results

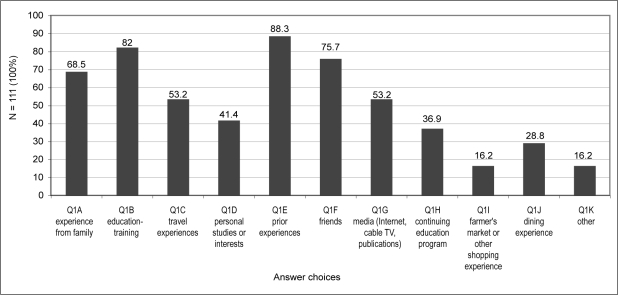

One hundred eleven nurses completed the survey—a response rate of 44.4%. Four of the items on the questionnaire (items 1, 2, 5 and 6) were multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank questions. Item 1 invited participants to reflect on “what they draw on” when they are caring for someone from a different culture (Figure 2). The questionnaire provided multiple possible answers; participants were asked to circle all answers that applied and to add other answers of their own. A large majority of the respondents reported that they drew on prior experience, including experience with friends and family, and on their education and training; more than half also included travel experience and information gained from the Internet or the news truyền thông.

Open in a separate window

Figure 2.

When caring for a patient (or family) from another culture, how do you know what to do? What do you draw on in caring for patients from a culture different from your own? How did you get your information about other cultures?

Participants were also asked to enumerate the different cultures, communities, or ethnicities represented by the patients they had cared for (Table 1). Although some respondents identified broad ethnic categories (Caucasian, Asian, African American, and Hispanic), the specificity and breadth of the responses given were unexpected and remarkable. Participants identified unique, highly specific groups or ethnicities, including Croatian, Russian, East Indian, Korean, Tibetan, Yapese, Hmong, Nigerian, Ethiopian, Brazilian, Nicaraguan, Cuban, and Colombian. Furthermore, their responses revealed that these nurses understood culture as going beyond ethnicity to religious groups, sexual orientation, and social class (eg, homeless). In this article, we have chosen to fully report the wide range of responses that participants listed.

Table 1

Responses from survey participants (n = 111) when asked to enumerate the different cultures, communities, or ethnicities represented by their patients

Patients described as:No. of patientsAsianAsian/East Indian, East Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Taiwanese, Japanese, Indonesian, Hmong, Malaysian, Korean, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Thai, Tibetan, Nepalese, Yapese, Trukese99Hispanic/LatinoBrazilian, Portuguese, Mexican, Nicaraguan, Latin Americans, Central Americans, Spanish, Cuban, Venezuelan, Colombian81Caucasian/WhiteWhite American, Italian, Scottish, Irish, European, British, Greek, French, Swedish, Croatian, Russian, German, North American, Eastern Europeans, Canadian, Bosnian65BlackAfrican American, Inner-city Black, Jamaican, African, Nigerian, Ethiopian, French-Creole57Middle EasternPersian, Arab, Palestinian, Afghani, Iranian, Iraqi, Sikh, Pakistani, Islamic34Pacific IslanderSamoan, Guamanian, Micronesian, Tongan, Palauan, Fijian, Hawaiian, Polynesian18Muslim10Jehovah's Witness10Native American/Alaskan9Jewish7Lesbian/Gay6Hindu5Catholic5Buddhist3Christian2Hearing impaired2Transgendered2Gypsy1Amish1Mormon1Homeless1

Open in a separate window

We suspect that this breadth and specificity reflects a population of nurses who are particularly socially and culturally sensitive, who recognize the unique attributes of patients beyond broad categories of ethnicity or race. We do not know if a similar specificity and breadth of responses would be obtained if our questionnaire were given to different health care professionals or administered in more rural or more socially conservative communities and agencies. However, this might be an interesting area to investigate in a future study.

In item 5, participants were asked to identify (without any prompts) what resources had proved helpful in caring for patients from other cultures. Respondents reported that interpreters, ethnically diverse coworkers, patients and their families, have been especially helpful to them. The range of resources cited by the respondents indicate that they appreciate the variety of resources that have influenced their care, including verbal and nonverbal communication mechanisms, charting, and other coworkers, such as clergy and social workers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Resources participants identified as helpful in caring for patients from other culturesa

ResourceNo. of participantsCoworkers52Personal experiences36Patient/family37ATT/language line35Reading materials31School/clinical experience10Internet/TV/radio7Social services6Travel4Clergy4Chart/documentation4Gestures/nonverbal communication2Continuing education2In-service2Pain scale1

Open in a separate window

a Fill-in-the-blank question with space for multiple responses.

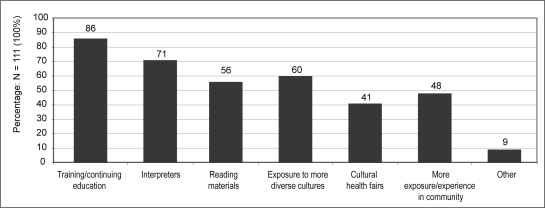

Finally, the nurses were asked what else they felt they needed to be able to provide more culturally competent care. Limited choices were provided for this item, and respondents were asked to circle as many as were relevant and to add other needs. Seventy-seven percent (86 respondents) reported that they wanted more training and continuing education on culture; 63% (71) said that there should be more interpreters. Respondents also perceived more “exposure to more diverse cultures,” as well as reading materials, as potentially helpful. When nurses were asked what would help them provide culturally competent care, a significant number of respondents agreed that training and continuing education would be helpful (Figure 3). Additionally, >50% of the respondents replied that interpreters, exposure to more diverse cultures, and reading materials would help them give culturally competent care.

Open in a separate window

Figure 3.

Needs to help provide culturally competent care.

Discussion

In this study, we were inspired to address some of the concerns raised in the Sullivan Commission Report3 concerning potential health disparities resulting from the lack of a diverse and culturally competent workforce. Our patient population, especially in Santa Clara, is unusually diverse, and our nursing workforce, although also ethnically varied, does not yet reflect the extent of the diversity of our patient population.

… nurses are drawing heavily on prior experience, including family experiences and experiences with friends and coworkers from different cultures.

In our study, we invited nurses from all inpatient units the Santa Clara inpatient facility to share their experiences in working with diverse populations. Specifically, we addressed the questions “What do nurses draw on when caring for patients and families who are from a culture different from their own?” “How do nurses know what to do when caring for a diverse patient population?” “What resources have been helpful to them in these kinds of situations?” “What other resources do nurses believe would be helpful in increasing their cultural competence?” These are critical questions to answer if we are to meet the goals of the Sullivan Commission. We have reported here our findings from the descriptive portion (multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank items) of the study.

Study participants reported working with an unusually broad and detailed range of cultures, and their responses revealed that many of the nurses understand culture as extending far beyond broad ethnic categories (white, black, Hispanic, Asian), to include individuals from specific, less common cultures, social groups, religions, and social class. We suspect that this reflects a unique level of cultural sensitivity and awareness. We do not know if a similar response would come from other health care professionals, from nonurban centers, or from more conservative states. Sampling from only one facility in one geographic setting is clearly a drawback, and we would recommend that this investigation be extended into other geographic and political regions.

In this study, we asked nurses to identify the resources that they find themselves drawing on when caring for a patient of a culture different from their own. Their responses confirmed our hypothesis that nurses are drawing heavily on prior experience, including family experiences and experiences with friends and coworkers from different cultures; a large majority also reported that they drew on their training and education, which suggests that schools of nursing are providing valuable preparation for working with diverse populations. A controlled, statistical study measuring the impact of such training on their graduates would be a worthy area of inquiry for schools of nursing.

The participants in this study found certain resources very helpful, including coworkers, translators, clergy, and communication by documentation in medical records. However, what stands out when one looks the question of necessary resources is the very clear message that nurses want more continuing education and more translators. These are areas where health care agencies can follow up immediately. We can expand translation services. We recommend that efforts be directed toward identifying the educational interventions and continuing-education approaches that are most effective in fostering cultural sensitivity. The participants in this study specifically indicated that more experience with diverse cultures would be especially helpful.

A significant limitation of our research is our purposeful decision to not include a demographic questionnaire because we wanted to make our study anonymous, thereby encouraging participants to be completely honest in their responses. Later, as we were analyzing the data, we found that it would have been especially helpful to know whether the cultural, linguistic, and educational characteristics, age, or religious ties of respondents were related to their perceptions and experiences.

Study respondents also brought rich, open-ended descriptions of their transcultural experiences with patients, their insights, and their challenges. The qualitative responses reveal an amazing breadth and depth of cultural sensitivity and creativity as well as the frustrations and challenges in addressing language, behavioral, and familial differences. These findings will be reported in a future article.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf, ELS, of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

The Great Army

You belong to the great army of quiet workers, physicians and priests, sisters and nurses, all over the world, the members of which strive not, neither do they cry, nor are their voices heard in the streets, but to them is given the ministry of consolation in sorrow, need, and sickness.

— William Osler, MD, 1849 – 1919, physician, clinician, pathologist, teacher, diagnostician, bibliophile, historian, classicist, essayist, conversationalist, organizer, manager and author

References

1. Grieco EM, Cassidy RC. Overview of race and Hispanic Origin: 2000: Census 2000 Brief [monograph on the Internet]. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2001 March. [cited 2009 Jun 3]. Available from: www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/c2kbr01-1.pdf.

2. State and county QuickFacts: Santa Clara County, California [Web page on the Internet] 2006. Washington DC: US Census Bureau;, updated 2009 May 5 [cited 2009 Jun 3]. Available from: ://quickfacts.census.gov/gfd/states/06/06085.html.

3. Briefing: missing persons: minorities in the health professions [monograph on the Internet]. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2004Sep 20 [cited 2009 Jun 3]. Availablefrom: www.kaisernetwork.org/health_cast/uploaded_files/092004_sullivan_diversity.pdf.

4. Clegg A. Older South Asian patient and carer perceptions of culturally sensitive care in a communityhospital setting. J Clin Nurs. 2003 Mar;12(2):283–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. De D, Richardson J. Cultural safety: an introduction. Paediatr Nurs. 2008 Mar;20(2):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Lambert VA, Lambert CE. Nurses’ workplace stressors and coping strategies. Indian J Palliative Care. 2008 June;14(1):38–44. [Google Scholar]

7. Harle MT, Dela RF, Veloso G, Rock J, Faulkner J, Cohen MZ. The experiences of Filipino American patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007 Nov;34(6):1170–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Juntunen A, Nikkonen M. Family support as a care resource among the Bena in the Tanzanian village of Ilembula. Vard I Norden. 2008 Sep22;28(3):24–8. Publ No. 89. [Google Scholar]

9. Liao MN, Chen MF, Chen SC, Chen PL. Healthcare and support needs of women with suspected breast cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2007 Nov;60(3):289–98. Erratum in: J Adv Nurs 2007 Dec; 60 (5):575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Gerdner LA, Cha D, Yang D, Tripp-Reimer T. The circle of life: end-of-life care and death rituals for Hmong-American elders. J Gerontol Nurs. 2007 May;33(5):20–9. quiz 30-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Searle C, McInerney F. Nurses’ decision-making in pressure area management in the last 48 hours of life. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2008 Sep;14(9):432–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Narayanasamy A. The ACCESS model: a transcultural nursing practice framework. Br J Nurs. 2002 May 9-22;11(9):643–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Sherer JL. Crossing cultures: hospitals begin breaking down the barriers to care. Hospitals. 1993 May20;67(10):29–31. [Google Scholar]

14. Parrone J, Sedrl D, Donaubauer C, Phillips M, Miller M. Charting the7 c's of cultural change affecting foreign nurses: competency, communication, consistency, cooperation, customs, conformity and courage. J Cult Divers. 2008 Spring;15(1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Nailon RE. Nurses’ concerns and practices with using interpreters in the care of Latino patients in the emergency department. J TranscultNurs. 2006 Apr;17(2):119–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Gebru K, Ahsberg E, Willman A. Nursing and medical documentation on patients’ cultural background. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Nov;16(11):2056–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a culturally competent model of care.

What is true about the nurse and ethnocentrism?

Ethnocentrism in nursing may prevent nurses from working effectively with a patient whose beliefs or culture does not match their own ethnocentric worldview. Unaddressed ethnocentrism can compromise nurse–patient relationships and lead to misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and insufficient treatment.Which of the following statements about empathy is correct?

The correct answer is 2 only. Empathy is the ability of the person to understand the feelings of others. It is something like putting yourself in the shoes of others. It allows the person to feel and understand the emotions that other is experiencing.Which of the following is the essential component The nurse must bring to the therapeutic nurse

There are five components to the nurse-client relationship: trust, respect, professional intimacy, empathy and power. Regardless of the context, length of interaction and whether a nurse is the primary or secondary care provider, these components are always present.Which of the following is the most important skill the nurse brings to the therapeutic nurse

The nurse understands that empathy is essential to the therapeutic relationship. Tải thêm tài liệu liên quan đến nội dung bài viết Which one of the following statements about the nurse and ethnocentrism is true? Cryto Eth

Post a Comment